Forests, Deforestion, Reforestion & Afforestation

/Updated. First Published 21 March, 2020

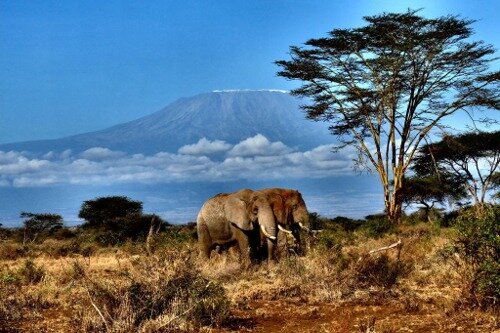

31% of the world’s land is covered by forest (World Bank), vital to climate, water, health, livelihoods and wildlife habitat and conservation. There’s approximately 3.04 trillion trees (Nature, 2015). What does afforestation and deforestation mean for travel, and can tourism help?

Agriculture, forestry and other land use sectors are responsible for 23% of global greenhouse gas emissions, largely resulting from deforestation and emissions from soil, livestock and nutrient management.

80% of the Earth's above-ground terrestrial carbon and 40% of below-ground terrestrial carbon is in forests, thus combating both deforestation and forest degradation is one of the most cost-effective ways to lower emissions. (Forest Carbon Partnership).

Each year more than 26m hectares forests are lost, an area roughly the size of the UK. This is double what it was in 2010, despite government pledges in the UN New York Declaration on Forests signed in 2014, requiring countries to halve deforestation by 2020, restore 150m hectares of deforested or degraded forest land, and aim to halt deforestation by 2030. But The World Counts (hectare loss counter) estimates only 10% of rainforests will remain by then.

Deforestation is the loss of forest. Forestation is the establishment of forest.

Forestation may be reforestation - planting native trees where forest was previously – or afforestation – which it wasn’t.

The vast majority of loss is tropical rainforest, with dire effects on the climate emergency and wildlife, with the most valuable and irreplaceable tropical primary forests cut down at a rate of 4.3m hectares a year.

46% of all trees have been lost since the start of civilisation (Nature, 2015).

Over half of worldwide tropical forests have been destroyed since the 1960s (IUCN)

15 billion trees are cut down each year (Nature, 2015), more than 26m hectares /64m acres (Guardian)

1000 football fields every hour: the world loss of forest area, larger than South Africa, between 1990-2016 (World Bank)

Latin America tropics has seen the greatest losses of forest by volume (Global Forest Watch).

17%: Amazon deforestation in the last 50 years.

Brazil Amazon deforestation rose by 88% year-on-year In June 2019.

Africa has experienced the greatest rate of increase of loss of forestation.

16% loss in Indonesia of its tree cover, nearly 26 million hectares of forest, from 2001 to 2018.

15%: the amount of global greenhouse gas emissions for which deforestation is responsible. (Forest Carbon Partnership).

1.6 billion people whose livelihoods depend on forests are impacted by forest degradation each year. One billion of them are among the world's poorest. (IUCN)

90%: The amount of global deforestation driven by agricultural expansion (FAO, 2021).

Deforestation and forest degradation are the second leading cause of global warming, which makes the loss and depletion of forests a major issue for climate change (Forest Carbon Partnership). Gross tree cover loss between 2002-13 and 2014-18 resulted in average annual CO2 emissions increase in Brazil 26.7%, Sierra Leone 473% and Guinea 474.5%, West Africa’s increase due to increasing palm oil deforestation.

On the plus side, the rate of loss of primary forest in Indonesia slowed by nearly one-third between 2017-2018, due to consumer and aid donor pressure on companies and government relating to palm oil, helped by wetter weather reducing forest fires.

Causes of deforestation and forest degradation

Direct causes of deforestation may be natural, such as hurricanes, fires, parasites and floods, or human activity, such as agricultural expansion, cattle breeding, timber extraction, mining, oil extraction, road and other infrastructure development.

Causes of deforestation may also be indirect: political, socio-economic or even cultural, due to failures in governance, land rights, corruption, conflicts and climatic changes.

Most deforestation occurs as a result of human activity: The main cause of deforestation is agriculture and for forest degradation is illegal logging (WWF).

Deforestation for land use for agriculture such as livestock farming is the most damaging: trees may go to timber logging commercialisation, but not only is carbon absorption lost, but livestock create additional emissions, and as forests are set on fire, so is precious wildlife and its habitat.

In Brazil and Indonesia, deforestation and forest degradation together are by far the main source of national greenhouse gas emissions (Forest Carbon Partnership).

Amazon deforestation is mostly due to forest conversion for cattle ranching, to feed the global beef supply, plus soy production in Cerrado: intentional forest fires clear the land, most often unofficially: Under Brazil’s Forest Code, in force since 2012, in theory only 20% of land in forested parts of the Amazon can legally be converted for productive use by farmers. Yet, Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (Inpe) said in its 2019 satellite data showed an 84% increase in forest fires on the same period in 2018.

Such is the deforestion that the vital Amazon carbon store could flip from being an absorber of CO2 to a source of emissions as early as the mid-2030s due to escalating forest loss and slow growth (Nature magazine).

Indonesia’s palm oil deforestation sees 80% of its fires to clear land for palm oil plantations, driven by consumer demand for millions of palm oil-containing products. Indonesia is the largest palm oil producer in the world, supplying 56% of the world’s palm oil last year, its number 2 export after coal. Its neighbour Malaysia supplies a further 28% (Nikkei Asian Review, 2019).

Indonesia tropical rainforest deforestation also means the loss of biodiversity holding 10% of the world’s species of reptiles, birds, mammals, and fish, and vast amounts of carbon in soils and trees, much like the Amazon rainforest.

In Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire, which produce 62% of the world’s cocoa, deforestation-free chocolate is not only elusive, despite the ground-breaking Cocoa & Forests Initiative (CFI), it’s also driving species like forest elephants and chimpanzees to the brink of extinction (Ethical Corporation).

Côte d’Ivoire has lost approximately 90% of its forests due to cocoa cultivation since independence, according to Mighty Earth. Extreme poverty forces farmers to illegally plant in protected areas amid declining yields from aging cocoa trees, lack of good agricultural practices, and shrinking suitable land area due to climate change (World Bank, 2017).

Understandably, farmers feel the need to be compensated if they are not able to use their land for production and give up the right to deforest their land - but available carbon funding is limited, and it’s costly to move from monoculture to sustainable agroforestry sustainable projects which have slow pay back to contribute meaningfully to farmer income. Farmers are so far below the poverty line, even if offered support, they are not necessarily able to take up such options

With logging, trees are cut down to make timber, or cellulose for the furniture or paper industry. Centuries-old trees and other economically unattractive trees which may have important biological and ecological value get cut down. Wood cutting causes serious damage to the ecosystem, damages amplified by construction of roads for transporting timber. Plus, illegal logging drecreases the price of timber.

In recent years, warming temperatures due to climate change have dried out trees making them more flammable, where as their previous humid nature made it hard to burn lush vegetation which acted as a firebreak, then contributing more carbon dioxide, which fuels heating in a feedback loop.

Effects of Deforestation

As deforestation takes place, the atmosphere, water bodies, and the water table begin to dry out: all life on earth is affected by deforestation. Local climates are stripped of their moisture-holding flora and soils become stripped of nutrients and bacteria that help break down organic matter, leading to soil erosion, desertification, less crops and prone to flooding. Less water will run through rivers, smaller lakes and streams that take water from these dry up, and wildlife is impacted. And as trees are removed, so vast amounts of greenhouse gas emissions are released into the atmosphere from forests’ carbon sinks (Indonesia’s greenhouse gas emissions even temporarily surpassed the United States in 2015). This doesn’t just affect rural areas, but urban too, exaccerbated by further urbanisation (eg. Atlanta, Los Angeles).

Deforestation also creates a host of problems for local people. Smallholders and indigenous people who have inhabited and protected forests for generations are often in conflict with mass agriculture and brutally driven from their land. Human rights violations become everyday occurrences, not to mention health issues, for example damage from fires’ smoke and even an increase in disease: One study in the Amazon showed a 4% increase in deforestation increased the incidence of malaria by nearly 50%, because mosquitoes, which transmit the disease, thrive in the right mix of sunlight and water in recently deforested areas. (New York Times, 2012).

Plus, deforestation impacts global health: 25% of all modern Western drugs are actually derived from rainforest plants. Considering less than 5% of Amazon plant species have been studied for potential medicinal benefits, the cure for numerous debilitating diseases could be hidden in this incredible environment being cut down (Telegraph).

The Climate Crisis and Deforestation

Plants absorb Carbon Dioxide CO2 from the atmosphere, use it to produce food and in return give off oxygen. Destroying forests means CO2 remains in the atmosphere and in addition, destroyed vegetation will give off more CO2 stored as it decomposes. This will alter the climate of the region.

Protecting existing forests, particularly tropical, and restoring damaged wooded areas, has long been recognised as one of the cheapest ways of tackling the climate crisis.

Forests, a natural carbon sink, naturally take up around a third of anthropogenic CO2 emissions, but little investment support is available. However, deforestation contributes around a third of anthropogenic CO2 emissions: for which there is clear economic incentive (timber and agriculture, and often subsidised).

Many countries have embarked on tree-planting schemes, but so far these gains are far outweighed by the loss of existing forests. Even if they matched, tree planting does not compensate for the loss of standing forests, because new forest takes decades, if not centuries, to establish maturity for carbon absorbing uptake, plus established forest benefits more than just carbon – it’s also wildlife habitat and weather regulates in the whole ecosystem.

What is Redd, Redd+ or Redd++?

This is a UN climate change mitigation strategy.

REDD stands for countries' efforts to Reduce Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation.

REDD+ refers that plus conservation and sustainable management of forests, and conservation and enhancement of forest carbon stocks / ‘carbon sinks’.

REDD++ extends REDD+ by low-carbon but high biodiversity lands.

Unlike afforestation and reforestation activities, which generally cause small annual changes in carbon stocks over long periods of time, stemming deforestation causes large changes in carbon stocks over a short period of time. Most emissions from deforestation take place rapidly, whereas carbon removal from the atmosphere through afforestation and reforestation activities is a slow process.

This also conserves water resources, reduces run-off, prevents flooding, controls soil and river erosion, protecting fisheries and investments in hydropower, preserving biodiversity, cultures and traditions.

Engaging communities in collaboration as guardians of forests, given forestry concessions by government and supported by environmental NGOs, can support deforestation reduction aims and beneficial land use.

International Day of Forests & World Planting Day

To raise awareness and advocate for forestation, “World Forestry Day” was established in 1971 on the 21st day of March each year, becoming “Forest Day”, 2007-2012, with the International Year of Forests (2011) establishing the International Day of Forests by United Nations General Assembly resolution in 2012.

It came about by two scientists feeling the world was underestimating the importance of forests in mitigating carbon emissions and saw a glaring need for the latest forestry research and thinking to inform global policy makers and UNFCCC (UN Framework Convention on Climate Change) negotiators.

Each year on 21st March, various events celebrate and raise awareness of the importance of all types of forests, and trees outside forests, for the benefit of current and future generations.

Its background comes from Arbor Day (Arbour in some countries), a holiday in many countries in which people are encouraged to plant trees.

The first Arbor Day in the world was held by a Spanish village, Mondoñedo holding the first documented arbor plantation festival, organized by its mayor in 1594.

Arbor Day is usually observed in the spring, though the date can vary, depending on climate and suitable planting season. For example, in the United States, National Arbor Day is celebrated every year on the last Friday in April, though a state’s public laws may stipulate a different Arbor Day or ‘Arbor and Bird Day’ observance.

The UK's first Arbor Day was on the 6th February 2020, founded by Myerscough College in Lancashire, though National Tree Week around the last week of November is a celebration of the start of the winter tree planting season which sees around a million trees planted each year by schools, community organizations and local authorities.

What’s Forestation got to do with Tourism?

How can travel help with forestation and deforestation solutions?

Separating Afforestation/Reforestation and Carbon Offsetting

Forestation by tree planting is often directly associated with carbon offsetting, such as for personal travel flights. But carbon offsetting projects can be many other things not limited to tree planting, such as investment in renewable energy, or non-fossil fuel cook stoves.

And we think we should decouple the association of offsetting carbon - which we’re not a fan of as it doesn’t work for these reasons - from tree planting for biodiversity reasons – which does.

The most important thing to do is protect our ancient forests, and pursue reforestation or afforestation for biodiversity reasons – not for carbon offsetting for individual reasons.

For example, our partner lodge in Costa Rica, Lapa Rios, is a 930 acre private nature reserve on the southern-most tip of the Osa Peninsula, is Central America's last remaining lowland dense tropical rainforest. It acts as a wildlife corridor to Corcovado National Park and is home to 2.5% of the biodiversity of the world. Guests are invited to plant endemic tree species for reforestation – with over 10,000 planted to date! Through wise use of plants they also control erosion. Your stay as a guest can help contribute to this reforestion >

Tourism can support Forests & dependent communities’ livelihoods

Our Madagacar partner is located by Sainte Luce lush littoral forest packed with plants and animals that do not exist anywhere else in the world. But for the local people, its role as a source of food, shelter and income is more important than its beauty or scientific interest. Destructive practices such as charcoal production or slash and burn agriculture are common, and although these provide short-term benefits, they ultimately threaten both the forest and community’s long-term future, as well as that of the many endangered species.

With support and guidance from our partner, the community’s current priorities include developing a locally managed tree nursery to care for local endangered species as well as to provide a stock of fast-growing trees, and alternative employment options that do not harm the forest, such as developing reed plantations to support traditional weaving practices and generating ecotourism opportunities in the local area.

The support project has directly benefited 2,000 people through more sustainable livelihoods, with the wider benefits extending to the surrounding communities of 12,000 people – and around the world through the preservation of this unique environment. You can support the project and volunteer in conservation here.

Our partners in Kenya run the first REDD+ Carbon Project for Maasai communities: protecting from deforestation and degradation and supporting active forest, biodiversity and alternative livelihoods through REDD+ revenues to the forest-dependent local communities.

The 30-year project between 9 organisation partnerships under the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) and Climate, Community and Biodiversity (CCB) standards, protectes 1,000,000 acres, preventing 37 million tonnes of CO2 emissions. 2017 saw the first carbon credits sale, to Tiffany&Co.

Your stay includes a fee for its offset, and you can buy further carbon credits if you wish. Receive a full presentation of the projects at the MWCT headquarters if you book a stay through us >

Income from biodiversity conservation and sustainable agriculture

A stay at a protected area will support its forestation. Even here, at the world’s first private marine protected area, the island is also a forest reserve, Set up from conception to be ecologically, socially and financially sustainable.

Your thatched roof banda (bungalo) is idyllically set by the beach and forest, and you can take a guided walk and learn about forest ecology and explore the stunning coral rag forest around you, which harbours rare and endangered species, such as the giant Robber or Coconut crab, the largest land crabs on earth! Read more here >

Communities looking to productive use of land need to be incentivised to a new bio-economy that uses forest products in a way that can be developed sustainably without deforestation. This may be sustainable timber or agriculture, and encourage farmers to become carbon farmers too - capturing carbon, or indeed tourism and forest holidays.