Food: Waste Not, Want Not

/If we use food resource carefully and without extravagance we will never be in need.

I’ve been fortunate to attend Food Waste events such as Ambassador for Defra’s #YearOfGreenAction, part of their UK 25 Year Environment Plan. ‘Step up to the Plate’ was a symposium for the UK Government Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, with Ben Elliot, UK Government’s Food Surplus and Waste Champion, and Dr. Tristram Hunt, Director of the V&A, where the event was held with a private view of the exhibition, ‘FOOD: Bigger than the plate’. Here’s what we learnt.

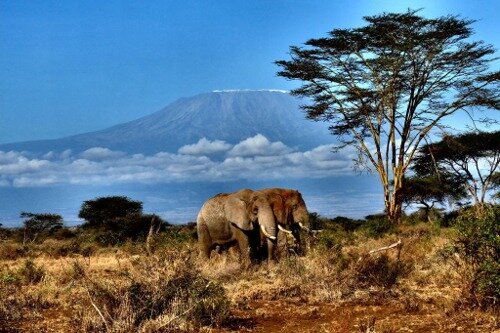

Food is an integral part of travel. Food draws people together, represents the local culture and has stories to tell. We try different foods, cultural dining experiences, and sometimes watch and learn how our food is prepared and made as part of our travel experience. How we produce food is a reflection of our values and the joy that food can bring.

But the way much of society is currently using food is disrespectful. Reducing our excessive demands on this Earth’s resources is a necessary thing for us to do.

At Earth Changers, we focus on maximum positive impacts through travel. With food a key component in tourism, where food is produced at scale, how can waste be minimised? Can tourism help us to respect the work that goes into food more and encourage us all to waste less at home? And how can it be used to support communities and actually contribute to global Sustainable Development Goal 2, Zero Hunger?

“There are so many who have so much, and so many who simply do not.”

The Big Picture

Food waste is an issue of which many of us are aware, and perhaps try to be conscious, at home. But it’s not just a waste of food that is the issue:

It’s food that someone else could be eating

It’s throwing away money

It’s a waste of the resources used throughout the supply chain, in the growth, production, processing, distribution, preparation, cooking and the disposal of the food. This includes the use of land, soil, biodiversity, water, energy, fuel, fertiliser, labour, time and investment – and carbon footprint thereof.

It’s not just about carbon emissions. Food that goes to landfill gets converted to methane, a greenhouse gas 34 times more intense than CO2. It also creates nitrous oxide, through refrigeration and fertilisers. In terms of emissions, food is the equivalent of every third car on the road.

And all this comes from our leftovers, which need not go to waste. In short, food waste is a completely unnecessary environmental, financial and social disaster.

When you start adding up those cumulative environmental, social and financial impacts that occur throughout the supply chain, the result is a huge global sustainability issue, significantly contributing to Climate Change - SDG 13 and the disastrous weather patterns we see. These destroy crop yields, changing species and the global food supply chain, of vital importance to creating Zero Hunger - SDG 2 and ensuring Sustainable Consumption and Production - SDG 12. In fact, SDG 12.3 target is:

“By 2030, halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses”.

The Size of the Food Waste Mountain

Global food loss and waste are estimated to amount to between a third and one half of all food produced (Global Food Waste Not, Want Not, Institution of Mechanical Engineers, 2013). That’s up to one in every two shopping bags!

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) that leads international efforts to defeat hunger estimates that one third of all the food produced for human consumption never reaches the consumer’s plate or bowl (FAO, 2016). That includes more than 50% of all the fruits and vegetables produced globally and around 25% of all meat produced – a vital source of protein, equivalent to 75 million cows. (FAO, 2018)

In fact, the world wastes enough calories to feed 1.9 billion more people the diet the World Health Organization says is needed to be healthy and satisfied.

Frighteningly, consumers in rich countries waste almost as much food as the entire net food production of sub-Saharan Africa. Europe and North Americans waste between 90kg-115kg per person per year; and sub-Saharan Africa, south and south-eastern Asia waste 6-11kg per year (FAO, 2011; 2015).

In the UK, it would take an area the size of the country of Wales to produce the amount of food that gets wasted. That food waste is worth £20 billion GBP every year and weighs 10 million tons, twice the weight of the whole population! It’s enough to feed 13 million people twice a day, represents £70 GBP per month for the average family with children and equates to 7 million tons of excessive food bought by homes alone.

According to the UN FAO, food waste is responsible for:

8% of global man-made greenhouse gas emissions. That’s the same as the entire global tourism supply chain’s emissions (yes, including aviation).

On a relative scale of country emissions, food waste would come out as the third highest country (after the US and China).Nearly 30% of all available agricultural land in the world - 1.4 billion hectares - is used to produce food which is not eaten.

The total cropland used to grow food that is never eaten almost equals all cropland in Africa (Environment Reports)

A global blue water footprint of 250 km3; the amount of water that flows annually through the Volga or 3 times Lake Geneva.

“Food – we need it to survive, but we take it for granted”

And this, in a world where 793 million people are hungry (1 in 9, or 11% of the world population experience chronic undernourishment), where one in five deaths are associated with poor-quality diets (FAO, 2018), and where the demand for food banks is intensifying, even in developed countries. Yet we produce enough food not just to meet everyone’s needs, but to feed 1.5 world populations (FAO).

We have centralised systems that move us away from buying food from local sources, and inadequate systems for distribution: so, food loss dramatically reduces the food that reaches people.

With the global population estimated to reach 9.9 billion by 2050 (+3 billion/30% from now), we need to ensure the world has the food resources available to feed everyone, yet cut food’s negative impact on the planet and develop sustainable ways to reduce waste from the farm to fork.

We can prioritize the reduction of food loss and waste as a way of improving people’s access to nutritious and healthy food: it represents a huge opportunity for individuals, companies, and society for a more circular economy.

What is Food Waste?

The UN's Save Food initiative, the FAO, UNEP, and stakeholders agree:

Food Loss refers to a decrease in quantity or quality of food in the supply chain between the producer and the market. This production, processing or distribution loss may be due to pests, problems in harvesting, handling, storage, packing, transportation or even institutional and legal frameworks.

Food Waste (a component of food loss) is any removal of food from the food supply chain which was fit for human consumption, or which has spoiled or expired. This is mainly caused by economic behaviour, poor stock management or neglect. For example, in the UK, up to 30% of vegetable crops are not harvested because their physical appearance fails to meet what is considered optimal in terms of shape, size and colour. Food may also be unnecessarily wasted due to “best before” quality suggestion.

When is Food Wasted?

Food Waste and loss may occur at any of the four stages of the food supply chain: production, processing, retailing, and consumption.

In lower-income countries, most food waste happens early on at the farm, during crop production and after harvest. Poor harvesting equipment leaves crops on the field, and poor infrastructure and inefficiencies in supply chain systems lead to post-harvest spoilage. Food may also be rejected due to high specifications of retailers only wanting specific standards. During storage and handling, foods may be affected by time delays in distribution, fungus and pests. People also spend a much higher proportion of their incomes on food than in developed countries, making it less likely that they will waste food at home (Environment reports).

As countries develop, supply chains become longer and more complex, but also more efficient and effective in harvesting, storage, transportation, and packaging. A lower percentage of food is wasted during production and processing, but as food availability improves, there is more waste during consumption. Food can reach the market but is thrown out before being used, for example if food is past the “use by” or “best before” dates. Unfortunately, these labels are not regulated and do not relate to food safety, but to manufacturers’ quality standards. We end up wasting food unnecessarily; we prepare too much and don’t eat leftovers. This happens at all points of consumption, whether at home, school, hospitals, restaurants, catered events or tourism.

Where is Food Wasted?

Countries’ food waste differs: Those more developed countries that are the most productive on a per capita basis tend to waste the most. As they tend to have diets richer in animal products, along with Latin America, the impact of the environmental cost of food waste is amplified, due to the food eaten by an animal during its lifetime. Per kilo, wasting meat has a much more dramatic impact than plant-based foods (Environment Reports).

In comparison, cereals have a high water and fertilizer footprint and high carbon intensity, as rice paddy agriculture emits a lot of greenhouse gas methane, as found in Asia.

Locally, food waste can differ further on a wealth basis. For example, in households in South Africa, food waste may be the same in volume, but it may be maize and rice in lower income households, as opposed to fruit and vegetables in higher income households. This in a country where 45% of the population could experience hunger within a day (Pinpoint Sustainability, 2019).

What Food Goes to Waste?

Food of higher cost is often wasted less due to its perceived value, whereas cheaper, perishable and more readily available foods tend to get wasted more often (FAO, 2011):

45% of fruit and vegetables that are grown, partly due to their more perishable nature.

45% of roots and tubers.

35% of fish.

30% of grains. Though when considering bread alone, it can be much higher as it goes stale.

20% of dairy and meat. Higher cost products, likely better valued and managed, and more likely used up as leftovers.

Distribution and location can be a factor of waste, especially with fruit and vegetables, for example having bounced in trucks for a long time on bad roads to be delivered.

Storage can also be a factor. For example, food will spoil more easily in hot climates unless refrigerated, but refrigeration is not always accessible or on, such as in destinations with government-controlled load-shedding, such as occurs in South Africa, Nepal or other countries.

Food Waste in Tourism

Tourism comes into contact with the food supply chain at most of its stages:

At the production stage, many destinations rely on subsistence agriculture, particularly in less developed countries. This may support and be supported by tourism suppliers (retailers) buying locally to feed tourist consumers (consumption).

There is even a whole niche of travel dedicated to agro-tourism, for example, wine, champagne, coffee or specific regional foods’ tourism:

> At Jicaro Island in Nicaragua, you can observe and learn the local and traditional methods of fishing, and watch the master chef in the open kitchen overlooking Lake Nicaragua. The freshly caught seafood supports the local fishermen economically, helps teach about sustainability, and creates opportunity for the cultural exchange with guests.

Many of our tourism supplier partners produce their own food so are involved in its processing, and/or buy local and organic, reducing food processing:

> Lapa Rios in Costa Rica offers a gourmet local culinary experience which has been developed based on cultural tastes and local and community-planted home-grown Central American endemic fruits and vegetables.

Likewise, tourism has different variables relating to food waste due to location: a city hotel has a very different set of requirements to a lodge in a rainforest or on a small island.

That said, there are typical ‘hotspots’ for waste where tourism operators can focus to reduce food waste, that you might like to be aware of to lessen your food waste impact:

Food preparation, such as greater trimmings, peelings, especially in high-end, luxury establishments for a more ‘particular’ look. Yet these are more likely to be used in stocks and sauces compared to lower budget hospitality.

Serving options. A buffet can significantly increase food waste compared to an a la carte restaurant where quantities are more controlled. On the other hand, more discerning, higher-end customers might demand more choices, which can also result in unintended food waste. Side dishes and condiments can be offered as options.

> At Nikoi Island in Indonesia, the menu is fixed to reduce food waste and focus on seasonality. It is home-made, organic and guideline-compliant, such as WWF sustainable seafood.

Spoiled food. Storage facilities and practices, stock control and purchasing practices, can all affect food waste levels. For example, can food be stored better, such as in resealable containers? Is food stored in the correct place? Need it take up space and energy in the fridge? Is there enough refrigeration space? Can things be frozen? (Did you know eggs can actually be frozen, in liquid form as opposed to in shells?!) Is produce stored at the correct temperature? (It’s cooler at the bottom of the fridge.) Could you buy less? Do beverages like carbonated drinks or sparkling wine go flat or go off? Can you get a stopper to prevent that happening, or buy wine on-tap? Do you date food so that you know whether you can use it?

Leftover plate waste. Does serving give overly large portion sizes? The US is well known for this, and it also happens more in medium and large-scale operations. With a more discerning clientele, higher end restaurants usually offer smaller-size portions, so waste less. Perhaps your hotel or restaurant offers different portion sizes or taster menus?

Ask for a small portion if you know you won’t want more or refuse the breadbasket if you don’t need it!

In a hotel, if you’re unable to finish a meal, you can always ask to take it back to your room, or ask the kitchen to keep it for you for later, discreetly if need be!

Zero Waste in hotels reports suggest 34% of food waste comes from customer plates, but the majority is from kitchens in preparation (45%) and spoilage (21%).

Love Food, Hate Waste – in Tourism

It’s important for tourism operations to understand where waste is coming from in order to manage and prevent it. They can follow the following process, as can you at home!

Measure and monitor: Collecting waste separately helps management understand where waste is arising. Is it in the kitchen? Is it spoilage? Is it behaviour oriented, such as serving overly large portions? Could that be reduced with training? Is it waste from consumers, maybe even the same common foods? Is it mainly meat, fish or perishables? Or is it a technical issue, such as an electrical chopper where edible food is not maximally used, for example the ends of courgettes or cucumbers? Once an operation has this data, they can convert it to financial cost to the waste.

Enable contributions by your team of questions and suggestions to learn.

Create an action plan to address the largest volumes and cost ‘lowest hanging fruit’.

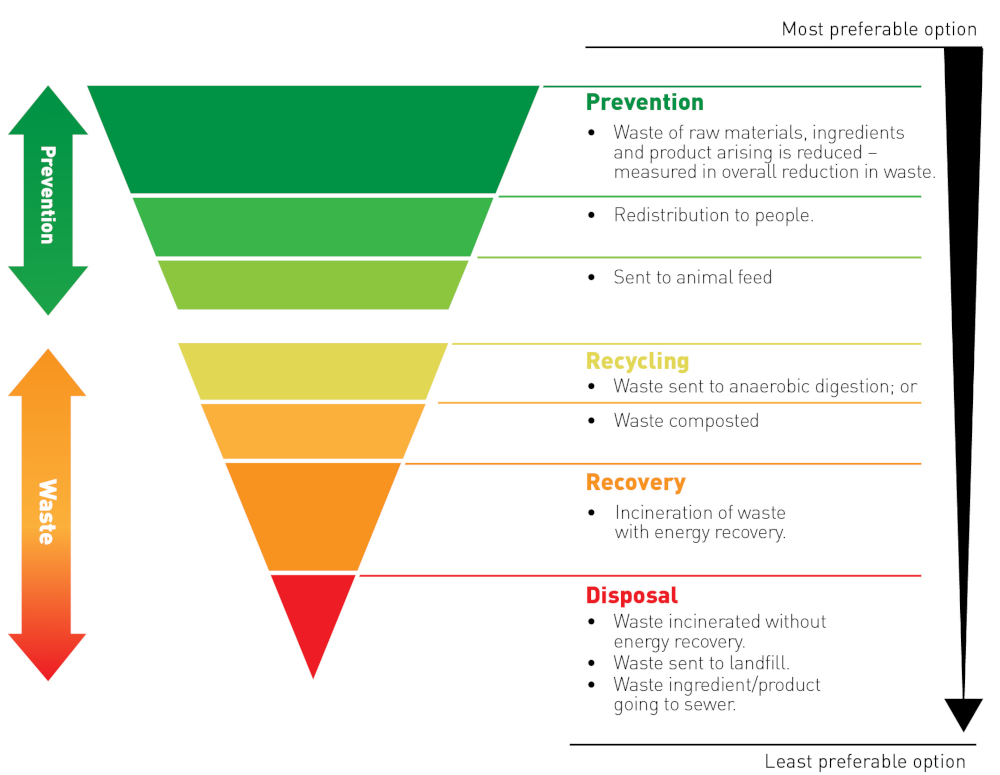

The Food & Drink Material Hierarchy: Prioritisation for Reducing Food Waste

Recycling or composting doesn’t come first! This diagram for the EU Directive on Waste (by WRAP: Waste & Resources Action Programme) shows the priority steps for dealing with waste to minimise the impact on the environment.

1. Prevent. This can also reduce cost of food purchasing, delivery and storage.

Ordering and planning can help prevent waste of ingredients, as can using pre-prepared, frozen or dried ingredients where feasible e.g. dried or frozen lemon slices in gin, or more imaginative menu options!

If you have a food preference such as vegetarianism, veganism, intolerance or allergy, by letting a hotel or restaurant know upfront you can help to limit waste.

2. Reuse. If food waste is not preventable, is it still edible? Surplus food can be separated from waste and redistributed to support a local community, staff or charity, especially important given the UN Global Goal 2 for improved nutrition, food security and zero hunger. The vein of a spinach leaf is highly nutritious, even if not used in high-end restaurants.

In turn, this supports communities to better Health & Well Being, SDG 3, and Education, SDG 4. Other surplus can be given to animals for feed.

For example, Grootbos in South Africa (where 45% of the population could experience hunger within 1 day) grow their own food, contribute to the local community and support local small holder farmers who produce food for them.

However, not all destinations are able to grow their own food due to their terrain or environment. And unfortunately, not all destinations are able to give leftover food to local people for reasons of litigation should someone experience health issues. In this case, tourism operations can challenge legislation to create a “Good Samaritan Act”.

3. Recycle. Send appropriate waste to compost or anaerobic digestion and create your own fertiliser to spread on land. This may be appropriate for inedible, uncontaminated fruit and vegetables. ‘Clean’ food waste can also be fed to animals.

Both Lapa Rios in Costa Rica and Jicaro Island in Nicaragua feed scraps to pigs. The methane produced from the pigs is even captured and stored to use for cooking staff meals!

4. Recover: You can incinerate contaminated and other remaining food waste (including meat) with a small-scale digester or send to an Energy from Waste (EfW) facility. This will burn the food waste to generate electricity and heat. Incineration without energy recovery is preferred to sending food waste to sewer or landfill due to environmental impacts and costs of treatment.

5. Dispose. Send to landfill and sewers. This is the least preferred option, and hopefully one completely avoided by following the above points, especially for destinations where waste facilities are limited, such as on an island or in a sensitive ecological area.

Changing Behaviour

In the UK, #GuardiansOfGrub – a new campaign by WRAP to cut food waste from farm to fork – is aimed at empowering professionals from across hospitality and the food service sector to reduce the amount of food thrown away in their establishments and about making simple, low-cost changes to the way food is bought, prepared and served. The sector is responsible for 10% or 1 million tonnes of the total food wasted in the UK each year, valued at £3 billion, with the cost of avoidable food waste varying between 38p and £1 for every meal it serves.

Where ever you want to create behaviour change in others, make it EATS!:

E – Easy. For example, make plates smaller, especially for buffets, or, just by removing plastic trays from canteens, you can reduce food waste by 18%, simply because people don’t load up their tray excessively. Equating to (endangered) species in weight can help understanding.

A – Attractive. Get people’s attention! Incorporate understanding of food waste in to design. E.g. The 50/50 bread packet suggests freezing 50% to defrost when required rather than it go to waste.

T – Timely. Planning helps translate good intentions into action.

S – Social. Tell people what others are doing, it brings out our human competitive streak!

Food Waste Targets

The FAO concludes that waste could be reduced from 24% to 12%.

To meet current needs, this means we need to grow 1,314 trillion kilocalories less than we do now. That’s enough calories to feed about 1 billion people, or the projected global population growth between 2015 and 2028. The UK aims to eliminate food waste to landfill by 205, and a 50% cut is the European Union’s goal for reducing food wastage by 2025.

Halving food waste would also roughly halve its environmental impacts. This could save an area of cropland equivalent to the size of all of Brazil’s cropland (78 Mha), as well as the same amount of fertilizer as used in all of Brazil (12 Mt per year) (Environment Reports).

What can you do to halve – or more – your food waste?

With thanks for contributions to Nicola Jenkin @nicolaruby of Pinpoint Sustainability, The Long Run, Defra and WRAP.